Since the publication of BlackRock CEO Larry Fink’s 2020 letter, environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investing has broken into the mainstream. Despite its size (103 billion USD), ESG investing has largely neglected the fixed income (FI) market, which remains dominated by sovereign debt. Investors who seek environmental and social outcomes (and can tolerate risk) should […]

Free Book Preview

Money-Smart Solopreneur

This book gives you the essential guide for easy-to-follow tips and strategies to create more financial success.

11 min read

This story originally appeared on ValueWalk

Since the publication of BlackRock CEO Larry Fink’s 2020 letter, environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investing has broken into the mainstream. Despite its size (103 billion USD), ESG investing has largely neglected the fixed income (FI) market, which remains dominated by sovereign debt.

Investors who seek environmental and social outcomes (and can tolerate risk) should incorporate sovereign bonds, particularly from emerging markets, into their portfolios.

This article overviews the key differences between ESG equity and FI investing and provides examples of material E, S, and G issues as they pertain to sovereign debt. It also highlights key challenges and opportunities of ESG integration into sovereign debt moving forward.

Stakeholder investing

Governments often deficit finance to provide services for their citizens. Nowhere is this clearer than the current COVID-19 pandemic, in which developed market (DM) and emerging market (EM) governments alike are running up their national debts in order to mitigate the public health and economic fallout.

Purchasing corporate bonds of certain companies, such as clean energy producers, may also yield favorable stakeholder outcomes. However, selecting such companies is a roundabout and time-intensive effort compared to purchasing sovereign bonds for the following reasons:

- Governments provide services that the private sector cannot easily deliver on the country scale (e.g. education, infrastructure).

- A government typically has more stakeholders than an individual company.

- The same dollar invested in sovereign debt is more likely to directly translate into public services/goods than in equity.

However, this statement presumes that the appropriate sovereign issuers are chosen, and in that selection process is where ESG can make its greatest contribution.

ESG in Equities vs. FI

“Because a bond cannot exceed its face value, fixed income investment centers on reducing downside risk – which ESG is uniquely positioned to assist”

Why is the FI market so behind the equity market in terms of ESG? It’s partly the result of the traditional view that government bonds themselves are risk-free assets.

Rating agencies such as S&P and Moody’s are beginning to integrate sustainability into their credit ratings. ESG integration in FI differs from equities in key ways:

- Unlike equities, a bond’s ultimate value cannot exceed its face value. This translates into greater focus on reducing downside risk with FI than maximizing upside potential. Since ESG provides insight into material risks not captured by traditional financial analysis, it may even be better suited towards FI evaluation than equities.

- Bondholders have less engagement opportunities relative to shareholders. At the corporate level, bondholders are unable to promote the adoption of ESG-related issues and/or voice other concerns at annual shareholder meetings. These opportunities are even scarcer at the sovereign level.

- Macroeconomic factors such as interest rates, inflation, and safe-haven flows have a stronger impact on sovereign credit yields than ESG risks.

Governance

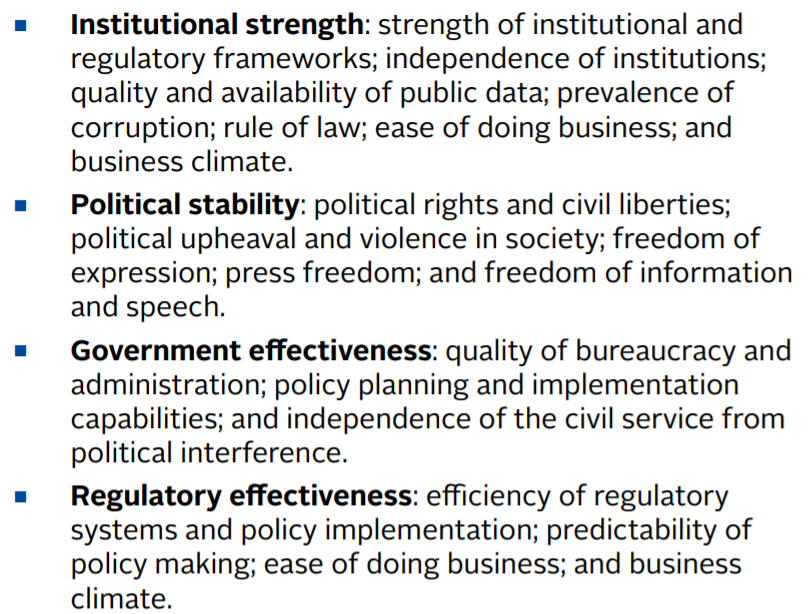

Governance issues are considered the most material of the three categories and have long been incorporated into traditional credit ratings of sovereign debt. The Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) group material factors into the following categories:

Source: PRI

Are DMs safe from governance risks? Not necessarily. Although they are considered to be more severe/prevalent among EMs, DMs are still exposed:

- A notable among these DMs is political gridlock, which can prevent governments from passing structural economic reforms, along with legislation that can reduce these issuers’ environmental and social risks.

- Certain EMs have proven resilient to governance and their associated credit risks. For example, Sri Lanka’s 2018 constitutional crisis briefly led to an increase in the country’s borrowing costs (measured by dollar-pay spread to Treasuries). In the end, the Sri Lankan Supreme Court upheld the rule of law, which was rewarded by a decline in the country’s borrowing costs of a similar magnitude.

Social

Social factors are a proxy for human capital development, which has been widely documented to spur economic growth. Some social indicators, such as demographics, living standards, and healthcare spending, are already factored into sovereign debt evaluation, albeit less so than governance factors.

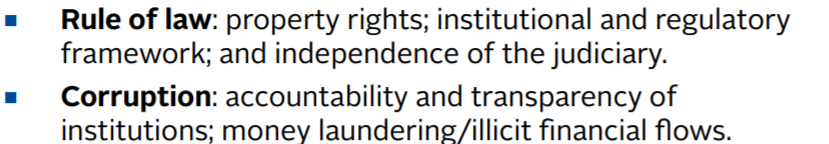

The PRI categorizes relevant social factors for sovereign issuers into the following:

Source: PRI

In the past, the relative strength of DMs institutions was assumed to mitigate social risks. However, economic inequality combined with rising sectarian tensions, in part a backlash to demographic changes, has led to the rise of populism across Western countries.

Concerningly, some of these governments’ bonds are considered safe haven assets, underscoring the need for investors to remain vigilant in their credit evaluations.

Environment

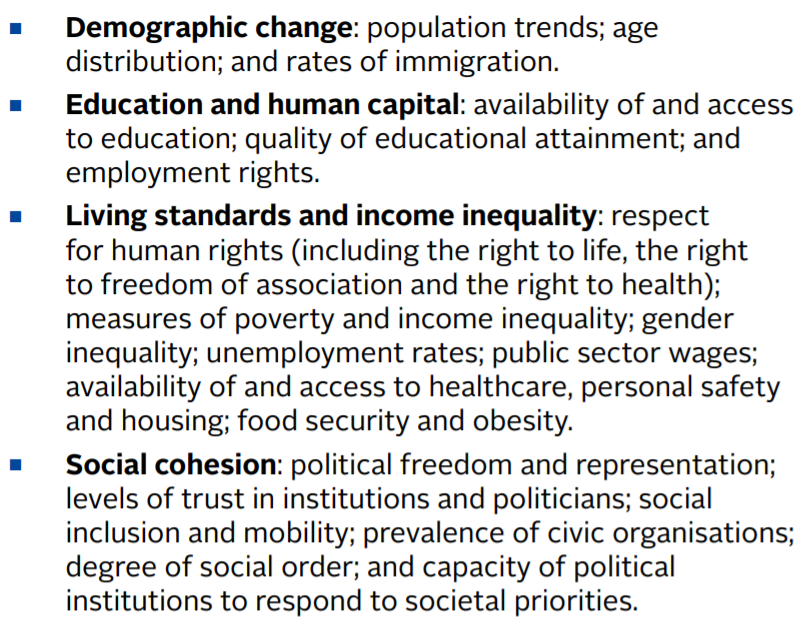

Environmental factors are typically considered the least material to sovereign debt issuers and thus are the least integrated. However, as climate change (and other global environmental issues) impact the world physically and socioeconomically, the E pillar stands to become increasingly relevant to sovereign debt investors. The PRI categorizes relevant environmental factors into the following categories:

Source: PRI

Natural capital management and climate change pose a series of unique challenges, such as timescale and transition risk:

- Risk Management Solutions (RMS) estimates wildfires in 2020 cost $7 to $13 billion in direct insurer costs across four US Southwestern states. The costs of extreme weather events may be even greater in the future if they permanently diminish the states’ economic output potential. The same can be said of developing countries, where changing weather patterns may lead to reduced agricultural output, which can translate into reduced economic activity and food insecurity.

- According to Planet Tracker’s 2020 report “The Sovereign Transition to Sustainability”, a high deforestation scenario which results in decreased rainfall could cause a 0.5% government revenue loss due to decreased soybean yields, Brazil’s primary export.

- 28% and 34% of Argentina and Brazil’s sovereign bonds, respectively, will be exposed to an anticipated tightening of climate and anti-deforestation policy in this decade. These figures emphasize the need to transition to sustainable agricultural practices, the primary driver of deforestation and land degradation.

- Rising sea levels in densely populated regions threaten to displace human capital, increase government expenditure, and lower economic growth in the long-run. For low-lying countries such as Bangladesh, sea level rise may hinder their ability to repay external debt.

- Countries whose balance sheets are heavily dependent on hydrocarbons (e.g. Saudi Arabia, Russia) are at a particularly high credit risk if they fail to quickly and effectively transition to a low-carbon economy.

ESG Sovereign Credit Ratings

“Good governance is therefore a necessary precondition to proper social and environmental scoring”

Are these findings discussed above supported by the data? Preliminary research by BlackRock indicates a significant relationship between ESG performance and sovereign credit spreads.

Because many of the pertinent sustainability metrics are slow-moving and only reported on an annual basis, the BlackRock team used a proprietary big data approach to work around this limitation. Their methodology is described as follows:

- BlackRock leveraged software that sorted through thousands of news articles and measures to search for 1) the frequency of keywords related to each ESG pillar and 2) the sentiment score associated with the content.

- Using a weighting system, the team assigned each issuer an overall ESG score to the bonds of 60 DM and EM issuers.

- In a hypothetical model, they found that ESG rating explained up to 25% of variation in sovereign spreads. The study also found that for all maturities examined, ESG had greater explanatory power than traditional credit ratings by agencies such as Moody’s’ or Fitch.

While innovative, such an approach is limited in application due to its reliance on news sources. Countries that score poorly on journalistic freedom and freedom of speech, as aforementioned in the Governance section, are more likely to produce content skewed in favor of the governments’ policies.

Unless analysts manually screen for biased content such as state-sponsored news outlets, BlackRock’s approach would result in artificially inflated ESG scores. Relying on outside sources is an option, but they may lack important “inside” knowledge and/or cultural context.

Good governance is therefore a necessary precondition to proper social and environmental scoring. Without ESG ratings that reflect the actual performance of a country across the three pillars, it is difficult to determine the extent to which ESG explains credit spreads.

Although ESG reporting in EMs has improved in recent years, investors will be limited in the number of EM issuers they can faithfully put their money in. This may create a situation in which the countries whose stakeholders are most in need of sustainable investment may be the ones investors must shy away from.

Engagement

“Investors may leverage engagement to push for improved ESG disclosure and alignment from sovereign issuers but must avoid the appearance of lobbying and/or interference in governments’ policies”

Sovereign debt investors may be able to leverage engagement with issuers to push for ESG transparency, among other demands. Several mechanisms already exist for engagement:

- In democracies, governments often meet with investors prior to the unveiling of annual budgets and medium-term fiscal plans in order to provide clarification and details.

- Governments and debt management offices (DMOs) may host roadshows to promote new bond issues, non-deal roadshow meetings, and ad-hoc events, although the latter is more common among safe-haven countries and large issuers such as China.

- Institutional investors have long conducted country research trips, which provide valuable opportunities to meet with various country stakeholders and assess the situation “on the ground.”

These forums are avenues for investors to push demands. However, engagement has had a mixed record thus far.

- In 2017, investors and a PRI Sovereign Debt Advisory Committee member started pushing Mexican central bank officials to improve their communications surrounding monetary policy decisions. These concerns were taken seriously, and in April 2018 the monetary authority announced it would start publishing the governing board’s voting records after monetary policy meetings.

- Nordea Asset Management suspended its purchases of Brazilian government bonds in response to the 2019 Amazon wildfires. With a then exposure to Brazilian sovereign bonds of 111 million USD, Nordea’s announcement caught the attention of Brazilian decision-makers, who subsequently invited its leadership to a meeting with government officials in Helsinki. Nordea was later backed by a group of institutional investors with a combined 4.6 trillion USD in assets under management (AUM). Despite their efforts, deforestation fires increased by 23% from 2019 to 2020.

- In 2020, a 23-year-old student filed a class-action lawsuit against the Australian government for failing to disclose climate-related risks to its sovereign bond investors. It remains to be seen whether the ongoing lawsuit will alter the AAA rating the bonds currently enjoy and/or change investors’ perceptions.

The COVID-19 pandemic provides an opportunity for investors to leverage their influence and push for greater ESG disclosure and sustainability practices. However, even the PRI acknowledges that investor engagement can be viewed as lobbying or attempting to interfere in governments’ policy choices.

This is a serious concern. In transactions between asset managers and banks in the Global North and sovereign issuers in the Global South, investors must avoid even the appearance of a neocolonial relationship.

Such interactions would be counterproductive to the goals of responsible investors. One can argue that government officials who are more preoccupied with appeasing foreign investors than serving their own citizens is a sign of poor governance.

Conclusion

ESG investment in sovereign bonds has lagged significantly behind equities and even corporate bonds. Currently, only a handful of ESG-aligned sovereign FI indices exist.

Chief among them are the JPMorgan Emerging Market (JESG EMBI) Indexes, Climate-adjusted FTSE Russell Global Government Bond Index (WGBI), and S&P ESG Pan-Europe Developed Sovereign Bond Index.

Nonetheless, this asset class is rapidly catching up.

An analysis by Charles Schwab indicates that EM allocation (specifically in US-dollar-denominated debt) to a fixed income portfolio can increase returns while providing diversification. This comes at the price of higher risk, but ESG can mitigate that.

Governance risks, followed by social risks, remain the most material in the context of sovereign debt, while environmental risks will become more relevant in the decades to come.

Several key challenges remain with sovereign debt investing. These range from unreliable/missing data to the dominance of macro factors to ethical concerns over sovereign engagement.

However, rising interest from investors and investors alike, coupled with increasing research into the area, bodes an optimistic future for sovereign debt. For investors who are willing to incur higher risk in hopes of higher returns, ESG investing in sovereign debt provides a valuable avenue to create tangible impact and chart a sustainable future.