This article was translated from our Spanish edition.

Opinions expressed by Entrepreneur contributors are their own.

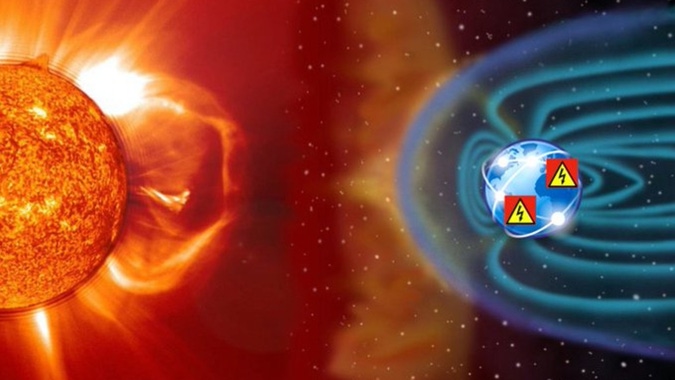

A new study claims that the next solar superstorm to hit Earth could trigger what they call the ‘internet apocalypse’ . According to Sangeetha Abdu Jyothi, an associate professor at the University of California, Irvine, this would prove catastrophic for global communications.

Sangeetha Abdu Jyothi vía Twitter

In the research , presented at SIGCOMM 2021, the annual conference of the ACM Data Communication Special Interest Group, the specialist explained that the submarine internet infrastructure would be very vulnerable to a future geomagnetic storm .

The Earth’s magnetic field protects humans from the solar wind , made up of electrically charged particles from the Sun. This magnetism deflects the solar wind towards the planet’s poles, creating the beautiful northern lights .

Every 80 to 100 years , these winds become solar super-storms and their current can damage long conductors , such as power lines , the study noted.

- It may interest you: Why the asteroid Psyche 16 is worth more than the entire global economy of planet Earth

Why would it be the ‘internet apocalypse’?

“What made me think about this is that we saw how unprepared the world was for the pandemic . There was no protocol to deal with it effectively, and the same goes for the resilience of the Internet , “Abdu Jyothi told Wired magazine.

The internet infrastructure essentially consists of long-distance fiber optic lines and submarine cables connected to repeaters . All are vulnerable elements to a solar storm of great magnitude.

“In today’s long-distance Internet cables, fiber optics is immune to GIC. But these cables also have electrically powered repeaters at ~ 100 km intervals that are susceptible to damage, ” explained Jyothi.

Repeaters are placed every 50 to 150 kilometers to maintain signal strength over long distances. If one of the repeaters fails, all wiring stops working, cutting intercontinental connections .

2 / A Coronal Mass Ejection (CME) involves the emission of electrically charged matter and accompanying magnetic field into space. When it hits the earth, it interacts with the earth’s magnetic field and produces Geomagnetically Induced Currents (GIC) on the crust.

[Image: NASA] pic.twitter.com/BO910bko5S– Sangeetha Abdu Jyothi (@sangeetha_a_j) July 29, 2021

“Our infrastructure is not ready for a large-scale solar event. We have very limited knowledge of the extent of the damage , “the professor added.

Transformers on the surface can be replaced in days or weeks to restore power. However, laying new submarine cables can take months , not to mention that several will most likely fail at once.

Thus, large regions and even entire continents would be disconnected from the internet for a long period of time.

In the document, Abdu Jyothi affirms that the economic impact of an Internet interruption is estimated at more than 7,000 million dollars a day , just in the United States. “What if the network doesn’t work for days or even months?” , the researcher sentenced.

Other catastrophic solar superstorms

On average, a massive solar flare occurs every 100 years , like those that struck Earth in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The last major solar storms occurred in 1859 and 1921 . The first was known as the ‘Carrington Event’ , as the geomagnetic disturbance was so severe that the telegraph cables burst into flames. In addition, the northern lights were seen near equatorial Colombia, when they are normally only visible near the planet’s poles.

Then came the Great Storm of May 1921 , when geomagnetic activity intensified electrical currents through telephone and telegraph lines, heating them to the point of combustion. In other words, telegraph and telephone stations , as well as various power stations and railway lines , burst into flames all over the world.

Strong currents disrupted telegraph systems in Australia, Brazil, Denmark, France, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The Ottawa Journal reported that many long-distance phone lines in New Brunswick were burned by the storm.